Sideways in Time: Marco Polo / Alexander the Great

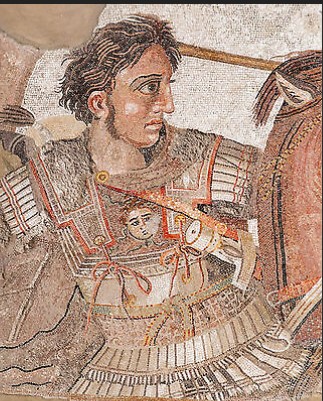

‘What is destined always happens. You can no more change the past than you can the future.’ If The Edge of Destruction came closest to realising Sydney Newman’s conception of a science fiction series with “no BEMs”, Marco Polo comes closest to fulfilling his brief of educational adventures in history. Across seven weeks in early 1964, audiences were treated to the history of the assassins, the explosive science of bamboo, the causes of condensation, and the lavish costumes at the court of Kublai Khan. At around the time Marco Polo was airing, Moris Farhi was commissioned to write a historical focusing on another great man: Alexander the Great.

The result, Farewell, Great Macedon, stands alongside The Masters of Luxor and The Minuscules as the earliest “lost” stories. Thanks to a 2009 script book and a 2010 Big Finish adaptation it’s also one of the most accessible, a tantalising glimpse of a series that headed in a different direction, hewing less closely to Terry Nation’s distinctly BEM-stery template, and staying true to Newman’s original vision.

It contains numerous similarities to Marco Polo – not least, its subject’s curiosity about his time-travelling visitors, and his readiness to trust them one moment and think them murderers the next. But because Alexander is also king, he doesn’t hold just de facto power over the TARDIS crew, but also the power to condemn them to a lingering death, should they offend him. In short, he’s a more dangerous proposition than Messer Marco.

Equally, Alexander’s enemies, principally Antipater and Seleucus, are a more direct menace than Tegana, who is merely the servant of the Khan’s enemies. Here, much of the story revolves around Antipater’s plot to assassinate Alexander’s nominated heirs and to pin the blame on the TARDIS crew, adding a neat dimension of murderous intrigue to the story. I think this tends to give the antagonists’ plot a bit more consistency and peril than Tegana’s slightly Wily E Coyote-ish attempts to derail Marco’s travels.

The downside is that this is far more static than Marco Polo’s continent-spanning adventure. Most of it takes place just outside the great city of Babylon. There’s a gorgeous opening sequence of the famous Hanging Gardens with plants wired for sound. But after that, there’s a lot of urgent declaiming in various tents, plus plenty of (presumably) educational sequences of Barbara explaining the Ishtar Gate, Alexander’s life story, gift-giving ceremonies, how to walk on hot coals, wrestling matches and anachronistic medical interventions (including the invention of the iron lung). The script is charming enough to remain engaging throughout, but it’s not difficult to see why six weeks of murderous vegetation, killer frogmen and hypnotic brains was a more enthralling proposition: no wonder at one point, ‘The Doctor had lost interest in Barbara’s impromptu history lesson.’ But the script’s oddest diversion is the Doctor’s very Christian meditations on being called to sit at the right hand of the Almighty when his old body wears a bit thin.

Apparently, Farewell, Great Macedon was abandoned when Farhi felt David Whitaker’s requests for rewrites would rob it of historical accuracy. If Farhi’s memory is correct, I wonder when this might have originally aired. My guess is in place of The Aztecs, largely because its final episode includes a lengthy discussion on the ability to change history. Here, it’s Susan who is the arbiter of temporal inviolability, and Barbara who is adamant on her knowledge of the events surrounding Marco’s death, and it’s the Doctor and Ian who decide they must at least try to intervene – in the Doctor’s case because he once took the Hippocratic Oath and cannot stand by and let a man die. Susan is emphatic, ‘History will not allow itself to be changed.’ And, in the end, Alexander rejects the chance to live and embraces death, conveniently cutting this particular Gordian Knot.

I suspect ideas in this story – vicious and murderous plotters trying to frame the time travellers, and the dilemma of historical intervention – found their way into John Lucarotti’s second script. Or perhaps both Lucarotti and Farhi were working in some of Whitaker’s ideas – in the same way that both Anthony Coburn’s The Masters of Luxor and Nation’s The Daleks include some common themes. Either way, they are more thoroughly and dramatically brought to life in The Aztecs, a story which also neatly bypasses the need for strict historical accuracy through not including any real historical figures.

While it’s not true to say that Marco Polo and Farewell, Great Macedon entirely stand apart from later historicals, once Dennis Spooner comes on board with The Reign of Terror the history books are largely secondary to historical literature, and personages like Nero and the Greek heroes are treated with much less reverence than either Marco or Alexander. The pleasure of most of the later historicals is their knockabout fun rather than their admirable accuracy. Farewell, Great Macedon is a relic from a moment when the show was pivoting away from its original brief. It’s nearly impossible to picture this being made at any point after mid-1964.

Next Time: The Keys of Marinus / Dr Terrors House of Horrors

Sources: Farewell, Great Macedon (Moris Farhi, 2009); Farewell, Great Macedon (Big Finish Productions, 2010).

One comment