All the Poirots – ranked Part Three: The A Listers

The final instalment in my Top 40 countdown of all of Dame Agatha Christie’s Poirot novels and stories…

The A-List

10. After the Funeral (1953): One of my long-time favourites. It’s another rancid family affair – the Abernathies are a particularly maladjusted bunch. The clueing and settings are very good, and the killer is well characterised with a peculiarly disturbing motive. Has a Marple-like gloomy, damp chill to it. Poirot on great form.

9. Sad Cypress (1940): The kind of domestic case in later years Miss Marple might have solved. Poirot’s investigation is neat and efficient, allowing the real focus to be on an unusually detailed run up to the murder plus the drama of a court case. Characterisation is some of Christie’s strongest, the clueing is good and the trial adds an extra level of jeopardy. The solution entirely surprised me. A complete, and oddly overlooked, success, less showy than an Orient Express or a Nile, but just as good.

8. The Hollow (1946): Mary Westmacott style murder story. Characterisation, as in Christie’s other 40s novels, is richer than before, and the crime itself and clueing feel almost incidental. Poirot appears fleetingly, but gets the best lines. The resolution is ingenious and credible, the overall effect is less showy than her Thirties Golden Age classics, but the upside is the punchline doesn’t feel like the whole point, and the story is more engrossing. A winner.

7. Murder on the Orient Express (1934): It’s easy to see why it’s one of the classics. It’s incredibly distilled, with no rushing about or second murders – perhaps the quintessential Poirot mystery. Poirot talks to all the passengers, sits and thinks, and announces his conclusions. On the downside, the ending is a bit cursory, and doesn’t entirely seem to fit with Poirot’s views: I get why the Suchet adaptation particularly made it much more of a moment. But apart from that, it’s practically perfect. And again, funnier than I remembered.

6. Cards on the Table (1936): One of Christie’s high concept ones: four detectives; four suspects, all previous killers. There are some great thriller moments (even if it gets a little daft towards the end), with astute characterisation and Poirot back centre stage after a few near-cameos. Mrs Oliver appears and is an instant hit. First rate.

5. Curtain (1975): As audacious as anything Christie wrote, with a genuinely chilling premise and a dark and ominous atmosphere of impending doom. Includes the greatest ever use of Hastings, and Poirot at his most ingenious. I’ve seen criticism that suggests the killer and victim are a bit under-characterised, but this seems to me to be a misunderstanding of who the final killer and his chosen victim really are. Right up to the end, even in sadly reduced circumstances, Poirot can bamboozle his old friend, and readers. A book fizzing with urgency, too – in the text, to prevent a murder. In real life, Christie staging her own curtain call in the anticipation of dying in the Blitz. It’s a magnificent achievement, poignant without being mawkish and cunning as a fox. The denouement by letter could have been a bit dry but Poirot recreates the crime and solution as effectively as before a drawing room audience. Bravo. There will be no encore.

4. Death on the Nile (1937): Poirot on top form even if at times it’s almost Fawlty Towers farce with loads of just-missed-me scenes of characters popping in and out of cabins. I think the denouement sacrifices a lot of credibility for cleverness, but I admire its nerve and it’s a first-rate puzzle mystery.

3. The ABC Murders (1936): Even darker than usual with Jack the Ripper style letters to Poirot and another twist that’s so simple but clever it’s become almost a cliché. I found the seemingly random psycho killer particularly creepy as a kid, given my initials. Luckily I didn’t live in Macclesfield (true generally).

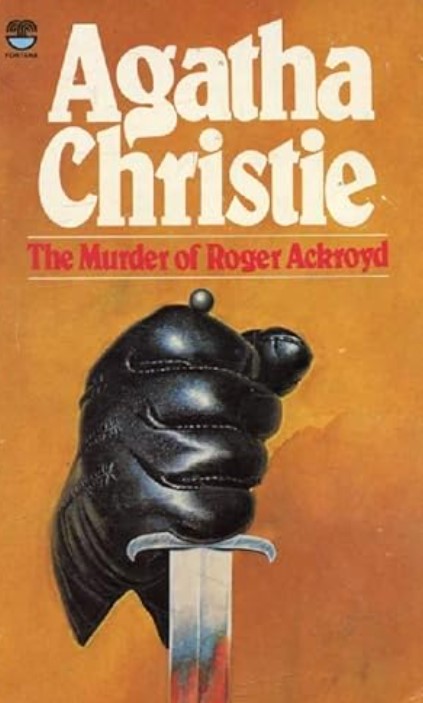

2. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926): Replacing the Woosterish Hastings as narrator with the drier, smarter Dr Sheppard was a wise move. His slyly confessional style is much more entertaining. Plus his critique of proto-Marple Caroline’s methods reflects my own feelings about Miss Marple herself. Through Sheppard’s eyes, Poirot also becomes less of Hasting’s “funny foreigner”: he’s still charming, and funny, but he also seems more distant, and more dangerous. Like the second Dr Who, all the funny tics are calculated to make people underestimate him. The mystery itself is rather more cleverly clued than the earliest Poirots, with the emergence of one of Christie’s techniques, the obsessive focus on a single out-of-place item (here, an armchair) that suggests the solution. Her writing style is also maturing. The characterisation is sharper, and there is one exceedingly amusing chapter where several suspects discuss the case over a game of Mah Jong. The reveal is exceptionally cleverly done, and is scrupulously fair: Poirot even points out the clues to the killer’s identity to the reader. And the final couple of chapters are truly chilling as Poirot stops grandstanding and skewers the killer to extract a confession. Clearly a masterpiece, and not just because of the cheek of the twist. I think this is the novel that proved Christie had plenty of tricks up her sleeve, and is probably the single biggest reason why she became a phenomenon.

1. Five Little Pigs (1942): A work of great maturity and sophistication, telling the same story from five perspectives, with distinct voices and compelling characterisation. Poirot is a chameleon, adapting his approach to each suspect in turn. The resolution is an astonishing sleight of hand, as facts repeated five times suddenly assume a new shape. This book is a masterpiece of the genre. Only the fatuous “little pigs” rhyme grates. Wish they’d stuck with the US title Murder in Retrospect. Clearly Christie is thinking of “painting” in both the book’s subject and structure: each retelling of the story acts like another layer, carefully applied with a palette knife to create the full picture. This one belongs next to Amyas Crayle’s paintings in the Tate.

One comment