All the Miss Marples – ranked

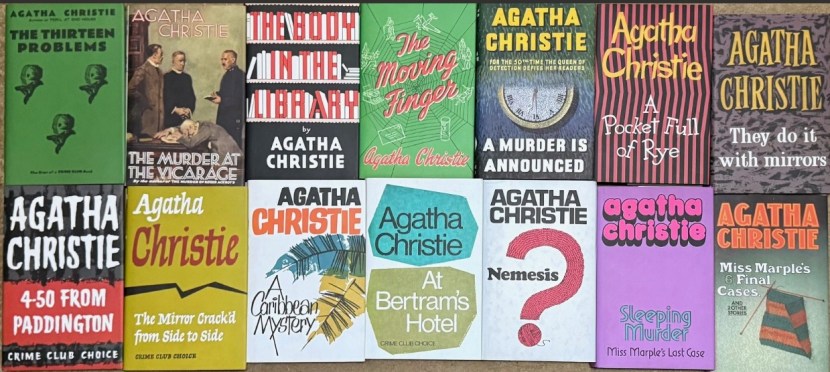

In 2024, having completed all the Poirots, I read Dame Agatha Christie’s complete Miss Marple canon, consisting of 12 novels and 20 short stories. My earliest memories of Miss Marple are of the terrifying ice-blue eyes of the Joan Hickson version, quietly eviscerating a murder. It’s clear why Christie suggested her casting: she personifies the pitiless retribution of Nemesis and gets to the heart of the character – Miss Marple isn’t a nice old lady twinkling gently (a mistake made by some of the other actors to have attempted the role). There’s something very frightening about her. “Creepy” is a word that continually crops up in these stories. While Poirot may be dedicated to the cause of justice, creepy he is not.

On the other hand, Poirot is a professional police officer and detective who usually does his own legwork. Miss Marple isn’t. At best, this means she has to call on the professionals to help her investigations. At worst, it means she just guesses whodunit based on her extensive knowledge of human nature (or curtain twitching), intuiting the solution like a more accurate Ariadne Oliver.

While this works in the early short stories, which are presented as puzzle mysteries for the Tuesday Club to solve over sherry, it can make some of the novels mildly frustrating, especially when the endings rely on absurd moments of entrapment and ventriloquism rather than Poirot nimbly stepping through the clues. Conversely, it means that the later Marple novels compare much more favourably to late Poirot, as Miss Marple’s woolliness is easier for Christie to sustain than Poirot’s meticulous precision, and her books lean into crepuscular atmosphere rather than sharp clueing.

As such, the short stories, which Christie herself stated “contain the real essence of Miss Marple” (in the foreword to the 1953 edition of The Thirteen Problems) are far more significant for Marple than the (often very lightweight) Poirot shorts are for him, and so I’ve chosen to rank them alongside the novels. Following Christie’s lead, we should expect the best of Miss Marple to be in the short rather than long form.

The Rankings – The C Listers

32. Ingots of Gold (1928, collected in The Thirteen Problems): Despite some promising hints of foreboding and doom, this is essentially a joke at Miss Marple’s novelist nephew, the pompous Raymond West’s, expense with a mystery designed to make him look like an oaf (and a pretty unconvincing explanation). A bit disappointing.

31. Motive v. Opportunity (1928, collected in The Thirteen Problems): Very slight and silly missing will story. I can’t help thinking the idea of a manipulative fake medium is a bit thrown away on this.

30. Sanctuary (1954, collected in Miss Marple’s Final Cases): Jewel robberies and murder sounds more like one of Poirot’s early cases than a Marple. This largely focuses on the rather stolid Bunch, with Marple little more than a cameo.

29. Strange Jest (1941, collected in Miss Marple’s Final Cases): Comical story about a hidden will, very tongue in cheek and slightly self mocking of silly and complicated invisible ink scenarios and so forth. Marple is now dashing about the country going to parties and visiting young people’s houses and is a far cry from the decrepit old dear of The Thirteen Problems.

28. The Case of the Caretaker (1942, collected in Miss Marple’s Final Cases): The barebones of a later and much greater Christie novel. Shorn of the novel’s vivid character and eerie atmosphere, this comes across as a very ordinary and slight mystery. The early version unearthed by John Curran is more impactful.

27. Miss Marple Tells a Story (1934, collected in Miss Marple’s Final Cases): Agatha Christie was the first person to play Marple, in a 1934 radio play which this adapts. It’s very much in the vein of the Tuesday Club cases with Mr Petherick seeking Marple’s insight to clear his client of murder. The solution is one of Christie’s not entirely plausible favourites. Mostly interesting for being a rare Marple first person narrative.

26. They Do It With Mirrors (1952): The evolution of Marple from armchair amateur to active detective continues as she steps into a more tradtional closed circle “country house” type mystery than usual. This one is frankly anaemic compared to the earlier novels, with a less sinister atmosphere and a pretty underwhelming cast of suspects, none of whom really makes much of an impression (barring, perhaps, an incredible, surly American). A couple of murders late on in the novel seem tacked on with little impact, and the climax is weakened by having it recounted in a brief memorandum rather than as proper action. The result is curiously flavourless for Christie, and represents a real dropping off in the wake of A Murder Is Announced.

25. The Four Suspects (1930, collected in The Thirteen Problems): One of Christie’s international espionage plots, but less fantastic than most. Even so, the solution to the mystery slightly strains credibility.

24. The Herb of Death (1930, collected in The Thirteen Problems): Amusing due to the pithiness of Dolly Bantry’s anecdote. The actual story is a little weak, as if Christie is starting to flag with the “armchair detective” style of Marple story – notably in future stories and novels Marple is a bit more mobile and active.

23. At Bertram’s Hotel (1965): “Miss Marple seldom gave anyone the benefit of the doubt; she invariably thought the worst.” A dismaying reversion to fanciful crime syndicates. While Marple is in this much more than The Moving Finger, her presence is far less impactful. Instead, she largely feels like a proxy for Christie to voice her own view on the world in 1965. And while that includes uncontrollable youths and train robberies, there’s also a rather clear-eyed view of getting older, and not being able to turn the clock back: “One can never go back; one should not ever try to go back – The essence of life is going forward. Life is really a One Way Street.” It feels almost of a piece with Third Girl – Christie dropping her two hero detectives in Swinging London and seeing how they get on. On balance, I prefer Poirot’s engagement with it than Miss Marple’s resigned observation of the ringing changes. The crime here is both ever-present and almost incidental, with lots of silly business about kidnappings, swapped number plates and (Surprise!) wicked actors. The actual murder is very guessable, and Miss Marple is back to intuiting whodunit. On the plus side, the characterisation is as strong as ever (especially “Father”, the genial but steely Scotland Yard inspector), and Christie’s nostalgic pleasure in Betram’s olde worlde charm is palpable.

22. Greenshaw’s Folly (1956, collected in The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding): Falls back on one of Christie’s favourite solutions, already key to more than one Miss Marple story. Not bad, but the characterisation and plotting is a little looser than her best.

21. A Christmas Tragedy (1930, collected in The Thirteen Problems): Very far fetched but nicely creepy, with Marple at her pitiless Nemesis best.

The B-Listers

20. Tape-Measure Murder (1941, collected in Miss Marple’s Final Cases): Why Christie didn’t stick with the title A Village Murder baffles me. It’s like calling one of her famous novels They All Did It. A shame, as it’s a very neatly observed and clued mystery, albeit the emerald heist angle is a bit of a stretch.

19. The Murder at the Vicarage (1930): Refinement of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd’s nosy village setting with overtones of The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Suffers a bit from some implausible clues and one red herring plot line too many (some silver plate thefts). On the plus side, the narrative voice of Reverend Clement is well sustained and the little scandals and rivalries of small town life are well sketched. Miss Marple here remains an unsettling snoop, a hovering presence rather than the central character, with an impact far beyond her relatively few appearances.

18. The Body in the Library (1942): Begins from a great hook of a first chapter, and includes many old faces from The Thirteen Problems and The Murder at the Vicarage (including Slack, Melchett, Clithering, the Bantries, Reverend Clement and Grsielda cameo with their baby). Miss Marple is “an old lady with a sweet, placid, spinsterish face, and a mind that has plumbed the depths of human iniquity and taken it as all in the day’s work” but is generally softer than previously (the first victim’s youth upsets her), and less unnerving despite an unladylike relish for the snap of the hangman’s rope. Some have criticised far-fetched elements of the plot, but if you can accept the police inviting Marple to participate in interviews and help organise a sting operation, almost everything else seems plausible. Characters are generally strong, including a proto-Jason Rafiel and a child crime enthusiast who amusingly has Christie’s autograph. A young layabout type is actually a war hero, Christie making a pointed comment about the horrors the young of the 1940s have had to endure. It’s a stronger and more focused work than The Murder at the Vicarage.

17. The Affair at the Bungalow (1930, collected in The Thirteen Problems): Christie again has fun writing in the airheaded voice of Jane Helier. In the telling the mystery is entirely baffling, but that’s rather the point. A clever end to the Tuesday Club murders.

16. The Moving Finger (1942): The premise is great: a small community, neatly sketched, torn apart by poison pen letters, which develops into classic Christie misdirection. It barely counts as a detective novel though: Miss Marple only appears in about a dozen pages towards the end, introduced as “an amiable elderly lady who was knitting something with white fleecy wool”, and intuits the solution immediately because she knows about “the different kinds of human wickedness”. As in previous Marple novels, the climax relies on entrapment rather than evidence. The narrator is Jerry Burton, who’s largely a superior Hastings but with an uncomfortable interest in someone who is described as being like a backwards schoolgirl. Overall: a superior Murder Is Easy.

15. 4.50 from Paddington (1957): Marple is back to puppet master, with most of the investigating split between Inspector Craddock and Lucy Eylesbarrow, one of Christie’s efficient and attractive working women. Their focus is the rancid Crackenthorpe family, another bunch of children in hock to a horrible tyrant of a parent (shades of Appointment with Death and Hercule Poirot’s Christmas). This opens with one of Christie’s best hooks: a murder witnessed by Mrs McGillicuddy when her train pauses alongside another, and which she breathlessly recounts to Miss Marple on her arrival in St Mary Mead. Marple’s initial investigation is brilliant, but I feel after these early chapters the book loses momentum (and Marple) for stretches. The climax is another of the risible traps Marple often falls back on in preference to actual evidence or deduction. Not up with the best of them, although the patriarch Crackenthorpe is satisfyingly horrible and his frequent complaints about the tax burden perhaps a bit of wry self awareness on the writer’s part.

14. The Thumb Mark of St Peter (1928, collected in The Thirteen Problems): A bit far fetched but very funny, especially Marple’s sharp asides to Raymond and the reaction to her earnest declaration about faith and fish. Lovely.

13. Sleeping Murder (1940s, posthumously published in 1976). “So Miss Marple’s got her finger in this pie.” Subtitled “Miss Marple’s Last Case”, and the first of the posthumous Christies. Another murder in retrospect plot, which makes it a neat fit alongside later novels even though it was written decades earlier. Unlike Curtain, this is very much not Miss Marple’s last case, and chronologically must occur in the 1940s or 1950s given the resurrection of Colonel Bantry and Miss Marple’s relative vigour. Nonetheless, it works as a kind of “missing adventure” because it reworks (or rather pre-empts) ideas explored in the earlier/later Marple novels: like the killer who strangles a woman, is inadvertently witnessed in the act, and unmasked when tempted to re-enact the crime; or a murder for love and a body buried in the garden. There are some great creepy moments, like the killer’s “monkey paws”, but like some other Marples it suffers because it’s obvious from what she says that Marple has already intuited whodunit, and so the youthful married leads’ investigations seem a bit redundant. This faint redundancy hangs over the whole book: whereas Curtain helps end Poirot’s investigations on a high after the disappointing Elephants Can Remember, Nemesis already felt like a great send off for Marple.

12. Nemesis (1971): “That old lady gives me the creeps.” All the hallmarks of very late Christie, with rambling scenes that go on forever, turns of phrase repeated by different characters (indeed, all the characters speak in the same voice – presumably Christie’s, as she dictated), a murder in retrospect, woolly clueing and quite guessable. This works better than Elephants Can Remember, because it isn’t quite as repetitive, and because it has the miasma of a horror novel with a curiously oppressive sense of menace that offsets some of the absurdities (murder by landslide). Miss Marple lives up to the book’s title, and it’s pleasing in her final (chronological) appearance to see her return to the characterisation of The Thirteen Problems – “the most frightening woman I ever met” according to the Home Secretary Reginald Maudling (and he works with Mrs Thatcher). Technically it’s the weakest Marple novel, but for anyone who enjoys the character it’s perhaps her finest hour.

11. Death by Drowning (1931, collected in The Thirteen Problems): The last of the thirteen problems is a transition to the later style of Marple stories where she becomes an active detective on a live case rather than a drawing room problem solver. True, all of the actual legwork is done by Sir Henry, but Marple already knows the solution. You could see how this could have developed into an interesting partnership – Marple as the Holmes character, Sir Henry as the Watson or Lestrade off finding clues and returning to the cottage to report back. It’s a great close to The Thirteen Problems – Marple solves a murder, prevents an innocent from hanging and proves her value to Scotland Yard. If this had been her final adventure, she’d already be Christie’s second most vivid invention.

10. The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side (1962): This is looser and funnier than many Marples, with a comedic sub-plot of Miss Marple’s battle of wills with her irrepressibly cheery and condescending live-in help. But there are also hints of mortality, as Miss Marple has a fall at one point, and is going deaf – which is mirrored in the broader decline of St Mary Mead, with widowed Dolly Bantry banished from Gossington Hall and a new Development encroaching on the green fields of the old village bringing modernity and the end of an older way of life. But for all that, she’s magnificent when it counts, saving a witness from probable death and getting a very Poirot-esque denouement scene as she reveals all at the scene of the first crime. This is poignant, with self-orientation and shattered dreams looming large. It’s obvious why this would be frequently adapted – the fading movie star glamour of Marina Gregg bursting into the St Mary Mead social scene is an obvious plum role for an Elizabeth Taylor. It’s a little bit brassy for a Miss Marple, and I think a little too easy to solve, but at least there are some proper clues and Christie’s insight to human nature is as sharp as ever. Sadly, there’s an entirely unnecessary and unsatisfactory eleventh-hour reveal that recalls a risible twist in a 1930s Poirot novel and drags this one down the rankings a bit.

9. The Companion (1930, collected in The Thirteen Problems): Miss Marple’s first tropical mystery – although she solves it all from Dolly Bantry’s dining table. Has the slight air of a Tale of the Unexpected in its tale of two women one of whom ends up dead. Very good.

8. The Blood-Stained Pavement (1928, collected in The Thirteen Problems): “I hope you young people will never realise how very wicked the world is.” More like it: such a horrid, clever idea Christie reused it in a novel. Again, it’s written like a picturesque ghost story with a grisly crime twist.

7. The Tuesday Night Club (1927, collected in The Thirteen Problems): The genesis of Nemesis, sitting cozily with her knitting while her pompous nephew and his artistic friend; an ex Scotland Yard commissioned; a clergyman, and a lawyer all jostle to bring their talents to bear to solve unsolved mysteries. Marple is sharp, incisive and pitiless towards people she deems “wicked”. This one is very good: Christie succinctly lays out the facts of a domestic tragedy for us, but Marple joins the dots.

6. A Caribbean Mystery (1964): “So you’re Nemesis, are you?” This is as close as Miss Marple has ever got to Hercule Poirot. The exotic backdrop recalls Golden Age Poirot visits to the Nile or Mesopotamia, and casting Marple as an active, even if elderly and infirm, investigator, following up leads, gently interviewing suspects and generally unravelling a crime – without either an indulgent senior policeman or a proxy at the scene – centres her in a way previous novels rarely have. Instead of immediately intuiting the villain because they remind her of someone in St Mary Mead, Marple has to examine clues and work out the solution. A far cry, then, from her early cases, and much more satisfying. Even the climax is a step up: still a “caught in the act” denouement, but mercifully free of ventriloquism or unlikely displays of personal heroism. There are some decent supporting characters, too: the refreshingly brusque Mr Rafiel, who tells Marple what he thinks and refuses to treat her like an old dear; his dodgy valet and an entertainingly pompous old major. On the downside, depictions of the black characters are very “stuck in their time”, and it gets a bit tiresome keeping track of the less vivid suspects’ various affairs. But in general, this is a very successful late Christie mystery and perhaps the last gasp of her classic-era greatness.

The A-Listers

5. A Murder is Announced (1950): Begins with one of the classic Christie hooks – a murder is announced in the local paper. Villagers turn up expecting some sort of murder game, only to witness an actual killing. They’re a well characterised bunch (including some sympathetic lesbians), and I enjoyed them all coming up with their own pet theories. Miss Marple is much more present and active than in previous books, although this does lead to a risible (but thankfully brief) moment at the conclusion. Clueing is very good, and I admire Christie signposting the solution and adding “You could get away with a great deal if you had enough audacity…” It’s a shame the climax once again relies on entrapment given there’s evidence to go on, but at least Marple gets to do the denouement to a gathered audience. I enjoyed it better than its spiritual predecessor Peril At End House, even if it isn’t quite as elegant as the best Poirots.

4. A Pocket Full of Rye (1953): Marple’s evolution from old lady sleuth to avenging fury is fully evident here, where her appearance is heralded by the colour rising “to Miss Marple’s pink cheeks… ‘That’s what made me so very angry. It was such a cruel, contemptuous gesture… It’s very wicked, you know, to affront human dignity’.” It gives what’s already a very good novel an extra bite, and the conclusion, which in a slight respect resembles the epistolary climax to They Do It With Mirrors, packs a real punch. The best novel for Marple, then. But the other characters are a pungent lot, strongly characterised, and for once the locum inspector, Neele (the name is interesting given a sub-plot involving philandering golf players), is almost as good a detective as Nemesis herself. The murders are peculiarly nasty, the nursery rhyme is consciously relevant to the story (unlike some), and the killer’s psychology is well illustrated. Lacking risible secret identities, ventriloquist powers and the entrapment that’s usually been key to resolving the Marple stories, I actually think this one has a slight edge over A Murder Is Announced (although this has always been vivid in my mind thanks to the peerlessly creepy Joan Hickson adaptation).

3. The Idol House of Astarte (1928, collected in The Thirteen Problems): “You make me feel quite creepy.” This is the business: it’s written like a horror story, albeit one with some sort of rational explanation – but even when Marple deduces the truth, unsettling questions remain. Could easily sit in one of those interwar ghost anthologies, or The Hound of Death.

2. The Blue Geranium (1929, collected in The Thirteen Problems): A brilliant, climactic synthesis of ideas from the first cycle of Tuesday Club problems – the creepy unexplained mystery with occult overtones; fatal attractions, and clever magic tricks, Dolly Bantry is a good foil for Marple.

1. The Case of the Perfect Maid (1942, collected in Miss Marple’s Final Cases): Excellent domestic mystery with brilliantly observed characters and told with much dry wit. Perhaps the most perfect Miss Marple story.

My partner is currently re-reading a lot of Christies and pointed out to me one passage that struck her this time – can’t remember the book, but Marple is described as a tall woman, not at all in keeping with the tiny actors who keep being cast in the role.