Category: 50 Years 50 Stories

1976: The Deadly Assassin

December 1976. In April, Prime Minister Harold Wilson resigned amid a whiff of scandal, to be replaced by James Callaghan. Across the hottest summer on record, the IRA continued its campaign of terror, while in November’s US Presidential election Gerald Ford – survivor of two assassination attempts – was defeated by Jimmy Carter.

December 1976. In April, Prime Minister Harold Wilson resigned amid a whiff of scandal, to be replaced by James Callaghan. Across the hottest summer on record, the IRA continued its campaign of terror, while in November’s US Presidential election Gerald Ford – survivor of two assassination attempts – was defeated by Jimmy Carter.

It’s been 21 months since the last blog entry. Tom Baker is now firmly ensconced as the Doctor, and the show’s popularity is equalling its 1960s’ heyday, with ratings regularly in the range of 10-12 million. From a 2013 perspective, this looks like a golden age. But from the moment it was broadcast, The Deadly Assassin became the most divisive story in Doctor Who’s history. It divided fans, appalled by Robert Holmes slaying the sacred cow of continuity. It outraged certain Conservative special interest groups, and it helped to convince BBC execs that the time had come to introduce some radical changes to the way the show was made.

As we’ve seen, as early as 1971 the production team was itching to abandon the UNIT format, but even by 1976, they hadn’t quite made the final break – four out of the first 11 Tom Baker stories feature UNIT to some extent, and for a viewer switching off the TV after The Seeds of Doom there’s nothing to suggest that you won’t be getting one or two contemporary Earth-based UNIT adventures per year for as long as the show is on the air.

Season 14 seems to confirm this when The Hand of Fear reliably returns the TARDIS to a familiar Twentieth Century science establishment, of the type we’ve seen in some shape or form every season since 1968. But there is a subtle difference – for the first time since The Sea Devils, UNIT aren’t on hand to assist the Doctor. In this respect, The Hand of Fear is a deeply unusual contemporary Earth story. And as with The Sea Devils, removing UNIT from the equation adds more jeopardy for the Doctor – he has no back up. There is no comforting Brigadier on hand to lay on a helicopter and five rounds rapid. Taken in context with Elisabeth Sladen’s departure making the national news, The Hand of Fear has a more uncertain tone than, say, The Android Invasion or The Claws of Axos. And knowing she’s leaving means that there’s the possibility that Sarah Jane’s burial in an explosion, possession, or wandering into a nuclear reactor could really be curtains for the character. Professor Watson’s final phone call to his wife illustrates that this time, the reactor really might go critical.

After all this, it’s a miracle that Sarah Jane walks out of The Hand of Fear alive (and it’s well known that producer Philip Hinchcliffe originally planned she wouldn’t). The audience is in a similar place as we are at Journey’s End, when Donna’s death has been foretold so often that we can’t quite believe she’s made it. But just as in 2008, there is a sting in the tail when the Doctor gets the call he can’t refuse, and forces his most loyal companion out of the TARDIS. Suddenly, all the rules have changed. The Doctor might have been summoned to his death. After all, the last time the Doctor visited his home planet he was “executed” and his companions had their minds wiped of all their travels with him. In that sense, his parting line to Sarah Jane, “Don’t you forget me”, has sinister overtones – because there’s the very real possibility that if he takes her to Gallifrey with him, Sarah Jane will suffer a similar fate to Jamie and Zoe, and be robbed of all her memories of this Doctor.

It’s hard to gauge just how jarring this must have been for a contemporary viewer, and how shocking a set up it is for the following story – but in my mind this is Amy Pond dissolving into the Flesh, or Rose Tyler telling us that Next Time we’ll hear the story of her death. The audience is being set up for something awesome.

The opening seconds of The Deadly Assassin make it clear that this is something very different from anything we’ve seen before: a scrolling caption that reminds us of the Time Lords immense power, that they look down on everyone else as “lesser civilisations”, and they love, above all else, “ordered calm”. In the space of a couple of sentences, Robert Holmes clarifies that the Time Lords are chauvinists whose whole existence is based around keeping everything in its place, and sets us up for a story that takes huge delight in its iconoclasm. However, all this is in danger as never before. The Doctor is about to do to the Time Lords what he’s done to so many other monsters: he’s going to bring their world crashing down around them. As he says, “Gallifrey is involved, and things will never be quite the same again.”

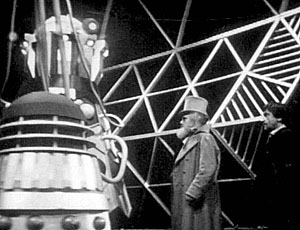

The Deadly Assassin is about as big a pay-off as it would be possible to deliver in 1976. After all, this is a series that’s already shown you the genesis of the Daleks. One of the only things that could top that about the Doctor’s first adventure on his home planet and a (long postponed) final battle against his Time Lord arch-enemy. Everything about The Deadly Assassin suggests what we’d nowadays call Event TV. It’s even positioned as the end of a mini-series of adventures, followed by a six-week gap – Steven Moffat must’ve been taking notes.

The first episode of The Deadly Assassin is an irreverent pastiche of British politics, complete with doddering old men, a broadcaster covering events with hushed reverence, a preference for pomp and ceremony over practicality, and, when the President talks about his resignation honours containing “some names here that’ll surprise ‘em”, a direct nod to Harold Wilson’s infamous ‘lavender list’. But Robert Holmes is just getting started. The Deadly Assassin tears down the veil that’s shrouded the Time Lords for so long, exposing their pompous moralising as the empty platitudes of a decrepit and defunct society. If there’s any doubt left that the Time Lords represent the deadening forces of conservatism, surely they can’t survive this. Holmes reveals that the entire world of Gallifrey, the whole Time Lord civilisation and power, is built on the Eye of Harmony, and can “neither flux, wither not change its state in any measure.”

In this story, Holmes finally seems to be unleashing the joyful anarchy that was apparent in his first script, The Krotons. The Time Lords introduced constraints into the Doctor’s universe, made him obey their rules, regulated his freedom and limited his adventures. The Deadly Assassin gleefully smashes all of that. Last time the Doctor left Gallifrey he was a prisoner, diminished. This time he leaves it as a liberator. That’s surely got to be a statement of intent: Hinchcliffe and Holmes finally getting out of the shadow of Letts and Dicks, and declaring that Doctor Who will no longer be looking respectfully to its past for inspiration, that the best is yet to come. This season has been an exorcism, leaving behind the Doctor’s ties to Twentieth Century Earth and Gallifrey and setting him off on new adventures.

Creatively, The Deadly Assassin is the climax of Doctor Who as it has been developing through the 1970s. The Doctor begins the decade cast down by the Time Lords and exiled to one place and time, or else forced to act as their puppet on Solos and Skaro. His return to Gallifrey as its saviour is therefore his ultimate triumph. But it’s also clearly positioned as his ultimate adventure – in the sense that it really feels like it could be his last. Having been stripped of UNIT and even Sarah Jane in the previous story, the Doctor is entirely alone. We’ve never seen him so vulnerable. He even says, “This represents the final challenge.”

The stakes are raised when we learn that the Doctor is going into battle against a Master who is no longer the comfortable “best enemy” of the Pertwee years. Without Delgado’s charm and wry sense of humour, the Master has been stripped to his basics; robbed of his attractive facade, he becomes the very image of Death itself. The dying Master is a culmination of the kind of crippled villains Robert Holmes specialises in. While it would be clearly wrong to equate disability with villainy, I don’t think that’s Holmes’ intent. Right from The Krotons, Holmes has been interested in monsters that are vulnerable or weak in some respect, suggesting that this makes them even more frightening. Inverting the usual Troughton formula, the Krotons are monsters under siege, surrounded in their base by potentially hostile aliens. Linx the Sontaran is stranded, alone, on one planet at a primitive stage in its history. The Wirrn are far from home and desperate. The Cybermen are a pathetic bunch of tin soldiers. Sutekh is trapped and immobile. Morbius envies a vegetable. The Master is horribly scarred, in pain and dying. All of them have one thing in common – a desperate need to survive at any cost. They will do anything to cheat death, and that makes them terribly dangerous. However wrong she was on every other count, Mary Whitehouse was right to recognise the Doctor is in extraordinary peril in the final cliffhanger: his body is lying dying on a slab and he’s fighting for his soul in a hellish world of the Master’s creation.

But mention of Mrs Whitehouse reminds us why, behind the scenes, The Deadly Assassin represents a kind of climax as well – because, on the basis of her hysterical complaints about this story, Philip Hinchcliffe was reassigned, and Graham Williams brought in with the explicit instruction to tone the show down. Of course, that doesn’t happen for another three stories – but we also know Hinchcliffe, with nothing left to lose, decided to overspend on The Robots of Death and The Talons of Weng-Chiang which had a knock-on effect on Season 15’s budget and landed his successor with a financial as well as creative crisis.

The legacy of The Deadly Assassin can therefore be felt both onscreen and behind the scenes. After a final, lavish mini-series of adventures, we get the cash-strapped Williams stories that, for all their brilliant attempts to overcome the need to avoid any kind of visual horror, look shoddy in comparison.

It’s a tragic irony that at the moment of their greatest confidence, when they were ready to set the TARDIS off on a journey into uncharted territories, free of the baggage of the last 13 years, Philip Hinchcliffe and Robert Holmes were brought down to Earth by the forces of conservatism they railed against in The Deadly Assassin, and never got the chance to fully reveal their vision for Doctor Who.

Even as the Doctor saves Gallifrey, he is being airbrushed out of his own ultimate victory. Borusa reminds us that time can be rewritten, that the Time Lords will remember Goth as the hero, preserving Gallifrey’s values of ordered calm against a fiend who glories in chaos and destruction. The Establishment triumphs, once again, while the Doctor runs. Nothing important happened today.

Next Time: “That’s what you are. A big old punk with a bit of rockabillly thrown in.” The Doctor faces the consequences of his actions in The Face of Evil.

1975: Genesis of the Daleks

It’s March 1975. In the three months since the last blog entry, the most important news in the UK has been the election of Margaret Thatcher as the Leader of the Conservative Party. Though in opposition for now, this is only the beginning for Thatcher. In the coming four years, she will prepare, she will grow stronger and, when the time is right, she will emerge and take her rightful place as the supreme power in British politics.

It’s March 1975. In the three months since the last blog entry, the most important news in the UK has been the election of Margaret Thatcher as the Leader of the Conservative Party. Though in opposition for now, this is only the beginning for Thatcher. In the coming four years, she will prepare, she will grow stronger and, when the time is right, she will emerge and take her rightful place as the supreme power in British politics.

And in Doctor Who we’ve got this. My first inclination when I got to 1975 on this blog was to avoid Genesis of the Daleks and go for something less obvious, (probably Planet of Evil, which I’ve always admired as a sci-fi retelling of M.R. James’s Oh Whistle and I’ll Come to You My Lad). But Genesis defies avoidance tactics. To an extent, it’s the hardest Doctor Who story of all to avoid – on top of the inevitable VHS and DVD releases, the endless satellite re-runs, the LP, a cassette, and an audiobook, it’s been shown five times on BBC One and Two. Many hundreds of thousands of people who might never have seen another Tom Baker episode have seen this. It even casts a shadow over the 21st Century series, called out by Russell T Davies as the opening shot in the last great Time War. In various polls, it’s invariably in the top five episodes of all time. In short, this is the biggest classic series story.

Genesis exerts a lasting fascination. The Discontinuity Guide claims Davros is the ultimate Doctor Who villain. But it’s more than that. Genesis feels almost like the ultimate Doctor Who story, one that goes back to the very roots of the series, and seems to subconsciously synthesise almost every major trend we’ve seen over the last 12 years. It opens almost uncannily like The War Games – a battlefield, shrouded in mist, with an unsettling mix of weapons from every point in Earth’s history. But this isn’t Earth – it’s an alien world. And then a Time Lord arrives. How much of this is incidental, and how much might have been deliberate on the part of David Maloney (director of this and The War Games) is a matter for debate. But if Barry Letts and Philip Hinchcliffe had, indeed, decided to go for a Patrick Troughton era cosmic horror vibe – and the idea of commissioning Gerry Davis to write a Cyberman story on a space station suggests that they must have at least subconsciously been thinking along those lines – then the opening of Genesis might be more than coincidence.

If the opening references one Troughton epic, then they must also have been thinking of the other. The last time we saw Skaro was in The Evil of the Daleks, another story that questioned the nature of the Daleks themselves. There, David Whitaker was taking the Doctor and the Daleks back full circle, for what was planned as their final confrontation. Genesis has the same sense of occasion. The opening conversation with the Time Lord is positioned as one last mission for the Doctor. The appearance of the Time Lord sets up a story that’s about impossible choices. When the Time Lord reminds the Doctor of “the freedom we allow you” the threat is obvious – he doesn’t really have a choice: he either does this, or he finds himself on trial again.

The difference between the Jon Pertwee and Tom Baker episodes is sometimes overstated – the beginning of Death to the Daleks is at least as eerie as this. But the overall tone of overwhelming horror; the way the camera dwells on corpses; the realistic poison gas weapons and machine guns, and the relentlessly horrifying tone of the opening episode are more disturbing than anything in the Pertwee years.

By its end, when Davros announces “we can begin” and the theme music crashes in, the audience has already been primed for something extraordinary. And for all it’s easy to criticise the giant clams, the ridiculousness of a tunnel between the Kaled and Thal domes, the cheat cliffhanger to Part Two, the fact that the most famous moments (the confrontation between the Doctor and Davros and the Doctor’s prevarication outside the Dalek nursery) are confined to the last two episodes. For all that, there is a queasy power to this story – the mercilessly brutal tone that Nation’s going to develop in Survivors and Blake’s 7 – that tends to crush any doubts that we’re watching an epochal story.

At this point, Tom Baker has also nailed how he wants to play the role: with a flippancy that seems permanently on the edge of erupting into anger, a tetchy, warning note in his voice that once each story boils over – here, it’s in the scene where Davros demands he tell the secret of future Dalek defeats and the Doctor bellows with rage, “No I will not!” He’s more dangerous than the third Doctor, someone to be wary of. While Pertwee’s Doctor frequently blew himself out in a rage against some hapless bureaucrat, when Tom Baker’s Doctor raises his voice, it’s frightening. He’s mercurial: eloquent and shrewd, volatile in temperament.

Against this permanently edgy Doctor, you need a villain who’s equally dangerous. Even before they meet, the Doctor and Davros are being set up as ideologically opposed enemies. Davros has discounted the idea of life on other planets: a pathologically narrow racialist ideology that’s going to be bred into his creations. Nyder claims Davros is never wrong, to which the Doctor testily replies that even he is occasionally wrong – Davros’s absolute certainty and conviction already being contrasted with the Doctor’s inquiring mind and self-reflection, which also neatly sets up the later scenes where the Doctor questions the morality of his own mission. That’s the unresolved conflict between the two of them – through his Daleks, Davros wants to be a god. Everything is an absolute: like Hitler, when he believes his people have proved themselves unworthy of his leadership, Davros simply condemns all of them to die. Meanwhile, the Doctor’s more worried about becoming a murderer, and can see some chance for good even in the most evil creatures.

Michael Wisher’s performance is extraordinary – a reflection of Tom Baker’s sudden switches from still contemplation to boiling anger. But equally praiseworthy is Maloney’s direction, including an astonishing moment in Part Two which references Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam as Davros’s finger reaches out to activate the Dalek’s self-control circuit for the first time.

So, you have an actor well on the way to becoming the definitive Doctor, pitted against a half-man, half-Dalek psychopath locked in a room together, and creating some of the most scintillating and memorable scenes in the entire series. You’ve got the Daleks as a sinister background force, gradually gaining in numbers and strength as the serial continues, until the point when they finally kill their creator and take control of the story. You’ve got some of the most dynamic direction in the show.

What about the Time War? Why did Russell T Davies pick out Genesis of the Daleks as the beginning of the end for the classic Doctor Who universe? What is it that makes the Time Lords so afraid of the Daleks?

We’ve previously seen that the Daleks are a force of change. Davros calls them the final mutational form, the ultimate creature. Their first story was originally titled The Mutants – their very nature is in mutation and change. They certainly changed the Doctor. At their most evil, they wanted to change what it meant to be human.

It must therefore be deliberate that at each stage, the Doctor’s mission is couched in the terms of stopping the development of the Daleks. Not killing them, but stopping them from developing, evolving, changing.

In comparison, as we saw in The War Games, the Time Lords are a force of conservatism: it’s why the Doctor left Gallifrey. They’re the lords of time, not its subjects – and change by its nature only happens to things that are subject to time. The Time Lords have placed themselves above the law, timeless and therefore unchanging, and they will stop any development that might threaten their own power.

I think that is the heart of the Time War – a conflict between a race that’s born out of chaos and destruction, tearing everything down and starting again, and one that values ordered calm above all – that, as we’ll see in the next blog entry, is by its very nature unable to change in any measure. At the end of the Time War, the Time Lords’ plan consists of bringing about the end of time itself, freezing the entire universe in an unchanging nothingness.

This conflict between order and chaos strangely resonates across Tom Baker’s tenure. The next producer will propose the entire universe is structured round the struggle between these two extremes, and the last plots Tom Baker’s entire final season around the idea of time’s arrow leading inevitably to disorder and the end of the universe.

Ultimately, the Doctor has already recognised that he isn’t infallible. So it follows that he rejects both the Dalek solution of extermination, and the Time Lords’ power to rewrite time and cheat the rules. The power of this scene is so indelible that Russell T Davies wrote the tenth Doctor’s fall, in the “Time Lord victorious” scenes of The Waters of Mars, around it.

The Doctor’s own nature, as a free agent, a catalyst for change, a mercurial element, shows it’s possible to escape from your own history, that just because you’ve come from a civilisation that is frozen in inaction doesn’t mean you have to accept that. The Doctor dares to change history every time he steps out of the doors of the TARDIS, and he dares to hope that the universe isn’t built around black and white choices, that even the Daleks, the most evil creatures ever invented, might have some capacity for good. But, unlike Davros or the Time Lords, he never pretends to have all of the answers.

That’s the lasting power of Genesis: the questions it raises about the nature of the Daleks, the Time Lords, the Doctor and the series are left tantalisingly hanging, to play on the imagination a long time after the story ends. It’s one of the reasons why people are still writing about it 38 years later.

Next Time: “The Time Lord has thirteen lives and the Master had used all of his. But rules never meant much to him…” The prodigal son returns home in triumph in The Deadly Assassin.

1974: Robot

December 1974. 20 months have passed since our last blog post. The most significant world event in that time is the resignation, in August 1974, of President Nixon. Meanwhile, closer to home, amid the escalation of the Troubles in Northern Ireland and a murderous IRA bombing campaign, Harold Wilson and the Labour Party are returned to power after two, inconclusive general elections: in short, a curious mix of change and more of the same. And that’s pretty much what we get from Doctor Who when Jon Pertwee, having played the Doctor for five years, bows out in June’s Planet of the Spiders.

December 1974. 20 months have passed since our last blog post. The most significant world event in that time is the resignation, in August 1974, of President Nixon. Meanwhile, closer to home, amid the escalation of the Troubles in Northern Ireland and a murderous IRA bombing campaign, Harold Wilson and the Labour Party are returned to power after two, inconclusive general elections: in short, a curious mix of change and more of the same. And that’s pretty much what we get from Doctor Who when Jon Pertwee, having played the Doctor for five years, bows out in June’s Planet of the Spiders.

The opening moments of Robot recap the Doctor’s third regeneration. As his two friends stand by, the Doctor, looking stricken, collapses to the floor, his familiar face and mane of white hair blurring into the features of a new, dark-haired character. If the production team were re-making the Hartnell era in colour, they could hardly have been more blatant in the reference to The Tenth Planet (the second in the space of one episode, given K’Anpo’s parting line). Not for Jon Pertwee impotently spinning away into the darkness.

The Power of the Daleks was a shocking break with the past, a conscious attempt to reinvent the series in the face of failing ratings, and which shared almost nothing in common with the predominant style of the Hartnell years. Spearhead from Space, while trailed by The Web of Fear and The Invasion, was doing much the same thing, setting up a whole new premise for the series as it went into colour – and, again, reformatting the show in light of the steep decline in viewers at the end of Troughton’s run.

But Robot is different. For a start, the ratings of Season 11 remained strong, peaking at 11 million. So, from the production team’s point of view, there was no burning drive for change. Look at the scriptwriters lined up for Season 12: except for Bob Baker and Dave Martin we can see Robert Holmes, Terrance Dicks, John Lucarotti, Gerry Davis and Terry Nation – writers who cut their teeth in the Hartnell and Troughton eras and were being brought in to do stories in the same, consciously retro style that Barry Letts and Dicks had established since Season Nine.

The only fly in the ointment is that Holmes (who by 1974 was clearly the best writer the show had got and was therefore Terrance Dicks’ natural successor as script editor) wasn’t entirely sympathetic to Dicks’ respect for the past. For example, he’d complained bitterly about having to write a historical for Season 11. Terror of the Autons – the only Pertwee script where you sense he’s really been let off the leash – takes a gleeful delight in being as horrible and disturbing to children as possible, like a Roald Dahl fairy tale.

But Holmes wasn’t yet in charge of the scripts, and new producer Philip Hinchcliffe was only shadowing Letts when the Season 12 was being plotted. It shows. Look at the season’s structure – the first and final stories set on Earth with UNIT, with the intervening episodes mixing space adventures and Dalek epics. Just like every season since 1972. In short, everything about Season 12 screams “more of the same.”

Look at the first scenes with the new Doctor, and you can clearly see Terrance Dicks referencing Jon Pertwee’s first story – a hospitalised Doctor, the TARDIS key hidden in a pair of shoes, references to his two hears, a mirror scene that’s been done in both previous regeneration episodes. It’s all highly amusing whether you remember Spearhead from Space or not. The big difference is in the last two transformations, the new Doctor has to convince his friends – and us – that he is the same man. Here. It’s never in any doubt.

Despite that, what’s really interesting about this transformation, though, is how closely it reflects the original changeover from Hartnell to Troughton. Much has been written about how the second Doctor is a kind of degraded version of the first, how the production team envisaged it as a kind of Jekyll and Hyde metamorphosis, and how Troughton’s costume is a tramp’s parody of Hartnell’s. The thing is, this is absolutely, equally true of the change from Pertwee to Baker. The fourth Doctor is a degraded version of the third, the elegant red velvet jacket, waistcoat and cravat replaced with a baggy corduroy coat, a cardigan and a neckerchief. Whereas the third Doctor was essentially serious about what he did (if not necessarily the way he did it), the fourth Doctor, with some arresting exceptions (like the moment when he snaps at Benton for letting Sarah Jane leave with Kettlewell), treats this whole adventure almost as a massive joke – and it’s going to be a characteristic of this new Doctor that he treats his adventures as amusing diversions in the vistas of eternity.

Moreover, Tom Baker is, like Patrick Troughton, a very physical actor. While Jon Pertwee loves being the solid rock around which a scene is built – standing steadfast, hands on hips, cape flapping, or lying in the famous death pose – Tom Baker is constantly moving. Watch the scenes outside the military bunker in Part One. As the Brigadier and Harry talk plot, the Doctor is digging about in the background, looking for clues and thereby dominating the scene even when he’s not centre stage. At the end of Part Two he gets an extended sequence where he practically dances around the lumbering robot. And in every scene, he’s doing something, messing with a prop or playing with his scarf. Terrance Dicks even has him inherit the second Doctor’s jelly baby habit from The Three Doctors.

That’s part of the genius of this story: that the plot is an excuse to get Tom Baker into a lot of situations where he can be interesting to watch. Baker always claims that the Doctor isn’t an acting part, and it’s therefore the quirks the actor brings that make him interesting. Essentially, Tom Baker plays the Doctor as if he were Tom Baker. Compare that to Pertwee’s self-confessed approach – playing the Doctor as if he were Jon Pertwee – and we see why these two actors are the ones most associated with the part, and why Tom Baker, though different in many respects, is the only classic Doctor to match Pertwee’s charisma and presence.

A similar thing has been happening with the companions. On paper, Sarah Jane Smith and Jo Grant are hardly high-concept characters (not, for example, super-smart space girl, or savage from the future on an Eliza Doolittle educational journey). Sarah Jane is, in theory, a bit more liberated than Jo, but both of them are independent only as far as it allows them to get into trouble and require rescuing. The reality is, it’s Katy Manning and Elisabeth Sladen that make the characters work. Sladen is particularly good at making Sarah Jane fearless and vulnerable at the same time, brazenly striding into danger until she realises that she’s in over her head. This means that Sarah Jane is an ideal companion: brave enough to follow the Doctor into any adventure yet scared enough to help sell the peril to the audience. Sladen is especially good at implying that Sarah Jane is constantly struggling between doing the sensible thing and walking away from the Doctor’s mad schemes, and excitedly joining in with them. You can see a perfect example of this in the final scenes of Part Four, where the Doctor offers her the chance to either remain on Earth with her job, or chuck it all for danger, and monsters, and life or death. The emotions flicker across her face for a moment before she, like us, commits to this new man.

The other really fascinating thing about Robot is that it’s the third story in the last seven that features no alien menace at all. Once again, humankind is the agent of its own destruction. The Doctor makes this moral explicit in Part Four when he compares the dead robot to human beings, “capable of great good, and great evil.” That’s typical of an increasing ambivalence about our species that’s only going to become more obvious as the new Doctor settles in: one minute he’ll be praising us as indomitable, the next he’ll be more alien and distant than ever. And at some point, he’s going to stop travelling with human beings altogether, for quite a long period of time, as though being forcibly confined with us for so long has been too much of a good thing. Certainly, from the moment he regenerates this Doctor is keen to be off. “I can’t waste any more time – things to do, places to go,” he says to Harry, off-handedly dismissing the whole UNIT era in a sentence.

In the end, Robot is as strange a story as the new Doctor it introduces. In some respects it’s a comforting continuation of what’s gone before, while in others it’s half turning its back on the Pertwee years. Only half, because even when Barry Letts and Terrance Dicks have both gone, Hinchcliffe and Holmes keep clutching on to UNIT, though less tightly each time the Doctor goes back to 20th Century Earth. For the most part, that’s a good thing: a mark of respect for the quality Letts and Dicks brought to the show. Unlike the last two regenerations, which threw the baby out with the bathwater and, as a result, lumbered the show with unsustainable formats, this time it looks like the incoming team might have learned all the right lessons, keeping the bits that have been effective while making the Doctor and his adventures less comfortable and familiar for the audience – but not too uncomfortable or unfamiliar.

While Tom Baker was making his debut, Pertwee was in another studio filming his swansong: life bizarrely imitating art as the old man and the new co-existed. And that’s Robot all over: a strange, transitory story that works like a roll back and mix between the two eras.

But, just as in 1966, there is an undercurrent that this new Doctor – and therefore the series – is suddenly much more dangerous than before. If the fourth Doctor really is a dark side of the third, an attempt to do a Troughton to Pertwee’s Hartnell, then might we expect the new era to reflect that darkness? If the biggest change between the Hartnell and Troughton eras was a move from a universe of wonders to a universe of terrors, might we expect that cosmic paranoia to re-emerge? You might think that if the production team really were taking inspiration from Troughton, we’d get futuristic space stations under siege, humans falling under the mental domination of alien intelligences and becoming their puppets, Cybermen and Cybermats spreading mayhem, an epic Dalek-myth story and monsters from under the sea rising to menace offshore rigs. Maybe even a companion wearing Victoria’s old clothes. But surely they’d never be that blatant?

Next Time: “There are some corners of the universe which have bred the most terrible things. Things which act against everything we believe in. They must be fought.” It’s time for the Genesis of the Daleks.

1973: Frontier in Space

March, 1973. The big news since our last story is that, fresh from his historic visit to China and the withdrawal of troops from Vietnam, President Nixon has been re-elected with a massive landslide. While in Doctor Who, we’re already three stories into the show’s 10th anniversary season – albeit, since Carnival of Monsters was made at the end of the ninth season and The Three Doctors was broadcast out of production order, Frontier in Space was actually the first story made as part of the 10th anniversary block.

March, 1973. The big news since our last story is that, fresh from his historic visit to China and the withdrawal of troops from Vietnam, President Nixon has been re-elected with a massive landslide. While in Doctor Who, we’re already three stories into the show’s 10th anniversary season – albeit, since Carnival of Monsters was made at the end of the ninth season and The Three Doctors was broadcast out of production order, Frontier in Space was actually the first story made as part of the 10th anniversary block.

1973 was a big year for Doctor Who: quite rightly since very few TV series reach that milestone. Even the iconic international success The Avengers only managed nine. Though The Three Doctors, with Patrick Troughton guest starring and with a poignant cameo from William Hartnell, was the big, season-opening headline-grabber, Barry Letts and Terrance Dicks deliberately conceived the whole of the 10th season as a celebration. And having used the season opener as an opportunity to publicly and definitively put the trapped on Earth format out of its misery – although as we’ve seen, in practice they’d already done so 12 months earlier – we get the sense that Letts, Dicks and their writers are delighting in the opportunity to have adventures in space and time again.

You’d be forgiven for mistaking the first episode of Frontier in Space for a Tom Baker story – it opens on the kind of spaceship set we’re going to see every year until Season 17 – until the third Doctor and Jo emerge from the TARDIS. Immediately, the Doctor begins trying to take readings, and work out where they’ve landed for his log book. Meanwhile, Jo, ever curious, goes off to investigate. Meanwhile, on Earth we learn that humankind is locked in a cold war with the Draconian Empire, and we quickly see another example of the Pertwee era’s obsession with the rise of East Asia: the enmity of China and the West we saw in Day of the Daleks is playing out again in the 26th Century, because the Draconians are basically Asian people.

Back in space, thanks to some kind of hypnotic sound, the crew have mistaken the Doctor and Jo for the feared Draconians, and locked them up. But the real culprits appear to be the Ogrons, who promptly steal the TARDIS and leave the Doctor and Jo to be tried as Draconian spies by the Earth authorities. After much protesting, the Doctor gets sent to an admirably multi-ethnic moon prison, and Jo gets locked up on Earth. At which point the plot thickens when the Master turns up in the guise of the Commissioner of Sirius IV to rescue them. A further trip to the court of the Draconian Emperor reveals that the Master is trying to provoke a war between the two empires, and a final chase to the planet of the Ogrons reveals that the real masterminds behind the plot are the Daleks. The story then ends, unexpectedly, on a cliffhanger as we realise that this is only part of a much larger epic

Frontier in Space plays out like Doctor Who doing James Bond – exotic locations, dramatic reversals in fortune, and a coalition of bad guys playing one empire off against another to cause a war just like every other 1970s’ Bond villain. In itself, that’s a reason to love the story. However, there’s more to it than that. After getting the old Doctors back, this is a celebration of the Doctor’s biggest enemies: it would have been unthinkable for Letts and Dicks to let the anniversary go by without the Master turning up. Delgado is on top form in what tragically became his final story: playing the role with a wry smile, and some magnificent comic touches (I particularly like the way he turns down the speaker as Jo witters on in her cell, so he can concentrate on reading The War of the Worlds). After three years, he’s as much a part of the show as the regulars, and his scenes with Pertwee and Manning are delightful, particularly in their final scenes on the Ogron planet when Jo’s able to resist his hypnotic powers and he’s forced to resort to more underhand methods to gain her cooperation. The three of them make a fantastic team – the only problem being, that’s not necessarily a positive trait for a villain. Though none of the later Masters is anywhere near as charming or as basically fun as Delgado, they’re at least more useful enemies.

In fact, when it’s revealed the Master is working for the Daleks, he gains a degree of menace that he’s lacked since the first half of Season Eight. If he’s willing to collaborate with them, maybe he really is bad. Though they’re in this for less than half an episode, this is the first time the Daleks’ appearance has actually been a shock – and the last, until Army of Ghosts pulls off a very similar trick of misdirecting the audience by having two of the big bads in the same story. Most shocking of all, the episode ends with the Doctor being shot, and forced to contact the Time Lords as the Daleks prepare their army for the conquest of the Galaxy. Which basically makes Frontier in Space a six-episode version of Mission to the Unknown. On top of the Daleks, we also get Draconians, Drashigs, Ogrons and the Ogron predator – five strange alien creatures and an evil version of the Doctor in one story, just like The Daleks’ Master Plan.

Many, many people have pointed out that with Frontier in Space and Planet of the Daleks, Letts and Dicks are consciously trying to recreate Doctor Who’s most famous epic. Some wag even came up with the umbrella title The Master’s Dalek Plan to describe the 12 episodes. These people are right. If I learned anything from the information text on Colony in Space it was that even in 1971 BBC executives still remembered the Hartnell epic as a high watermark for the show (or, at least, its ratings). But I think there’s more going on in Season 10 than just trying to re-make The Daleks’ Master Plan in colour (or In Color! For any Avengers fans reading).

Take the previous story: Carnival of Monsters. In it, the Doctor and Jo get shrunk down to an inch tall, and arrive inside a machine that contains all manner of strange alien beings. It sounds exactly like the kind of story they might have tried in Season Two. The next story is consciously retro to the extent that they bring back Terry Nation, whose last full script was 1965’s The Chase, to write it. Then after The Green Death – an anniversary celebration of UNIT that happens to include a WOTAN style world-conquering computer and some giant insects – we get the first story set in British history since 1966. On top of all that, whenever the third Doctor lands in space, the first thing that happens is that he loses his TARDIS (be it pinched by Primitives, falling off a cliff or snatched by the Ogrons). And he has a strange habit of wanting to work out where he is so he can program coordinates into the TARDIS. Meanwhile, Jo keeps wondering when he’s going to be able to get her back home. What we’re seeing in the Pertwee era, once it gets away from 20th Century Earth, is a reversion to the tone of the Hartnell years.

Season 10 isn’t just a celebration of Doctor Who’s history, it’s actively trying to make the show like it was in Season Two – the last time it was a runaway hit. The thing is, this works: the ratings for Season 10 peak at 11.9 million viewers, and average is 8.7 million, the highest since 1965. Letts and Dicks didn’t have a big new idea to replace the trapped on Earth formula. They just looked back to the last time Doctor Who was massive, and copied it. That’s why we’ve got the Doctor as an explorer who keeps losing his TARDIS. That’s why we’ve got a 12-episode Dalek epic. That’s why we’re about to get a historical that’s vaguely similar to The Time Meddler. That’s why Pertwee’s Doctor is a citizen of the universe and a gentleman to boot, and not a paranoid cosmic hobo on a crusade against evil.

That’s why, at its best, the third Doctor’s era is great: because it reimagines the glory days of Doctor Who in colour – and, when it’s on form, makes them even better. And I think it’s one reason why Barry Letts was so keen to involve Hartnell, even in a very minor capacity, in the anniversary, as a tangible link back to the era he’s paying homage to.

In future, other producers are going to look back to go forward, and they’ll pick different eras as their starting points. At some stage, the makers are even going to take the third Doctor’s era as their inspiration. But Barry Letts was the first producer to consciously do so, the first producer to appreciate the symbolic value of the show’s history to the British public, to bring back popular 1960s icons like the TARDIS, the Daleks, the Cybermen and the old Doctors. That’s why I think he’s one of the great producers of Doctor Who: because he saw that the original concept of the series developed by Verity Lambert and David Whitaker was so uniquely brilliant that he wanted to bring the tone of that show back. And because Barry Letts made this the default approach, I think the series will always come back: not just as bases under siege, or an Earthbound Doctor who works for the army and fights aliens but, first and foremost, as an adventure in space and time.

Next Time: “The old man must die, and the new man will discover, to his inexpressible joy, that he has never existed.” The fourth Doctor arrives in Robot.

1972: Day of the Daleks

January 1972. Across the world, the past 12 months have been marked by violent political upheaval, from coups in Africa and South America, to rebellion in Sri Lanka, and, closer to home, worsening violence in Northern Ireland and bomb attacks by a radical left-wing group called the Angry Brigade.

January 1972. Across the world, the past 12 months have been marked by violent political upheaval, from coups in Africa and South America, to rebellion in Sri Lanka, and, closer to home, worsening violence in Northern Ireland and bomb attacks by a radical left-wing group called the Angry Brigade.

At the start of its ninth season, Doctor Who tacitly acknowledges these events in a story which features a group of rebels with whom the Doctor sympathises, but cannot condone, and a moral which clearly states that the end does not justify the means; that violence only results in more violence, and no-one wins. The first episode begins with a crisis: World War Three looms, and this time the end of the world isn’t going to be at the hands of alien invaders, but human beings.

Even UNIT is struggling to keep up with the worsening situation, and while the Doctor hides away in his laboratory, tinkering with the TARDIS, the Brigadier has been placed in charge of security at a last-ditch international peace conference whose chair, Sir Reginald Styles, is apparently being haunted by ghosts.

Day of the Daleks is a pretty radical change from the stories of Season Eight. For a start, the glittery, glam sensibility of Terror of the Autons and The Claws of Axos is barely in evidence – despite the shiny-faced Controller and the gold Supreme Dalek. If anything, this feels like a throwback to the grim tone of Season Seven. The comfortable villainy of the Master is no more. Instead, we get time travelling human guerrillas and futuristic ape-men from a post-apocalyptic dystopia, like something out of a Planet of the Apes film (indeed, 1971’s Escape from the Planet of the Apes involved gorillas travelling back in time from a devastated Earth).

In short, this is all suddenly much more serious and grown up than last year’s episodes. Perhaps as a result, the Doctor spends much of the story on the back foot – bound and gagged, beaten and tortured, and finally, prone and mentally assaulted. We haven’t seen our leading man in this bad a way since he was interrogated on the parallel Earth – and just like in Inferno, the Doctor is once again cast in the role of Cassandra, struggling to convince the 22nd Century rebels that they’re condemning the Earth through their own actions. Until the end of the second episode, the audience is ahead of the Doctor, who is unaware that his greatest enemies are at the heart of what’s gone wrong with the future. Because the most important thing about this story is that the Daleks are back after a five-year absence.

It’s well known that Louis Marks didn’t originally intend this to be a Dalek story, and some have even gone as far as to say their inclusion is pointless. While it’s true that the production team can’t quite remember how to do them – the voices are off, and the director doesn’t shoot them from the most interesting angles – to suggest that this would be better off as an Ogron only story is odd. After all, if you could tell an alternative history story where Hitler won World War Two, why would you pick Mussolini? No, the Daleks are absolutely the right villains for this story, because they bring such a weight to the broken future. And although the production team don’t quite get the details right, they nail the tone – slave labour camps, a subjugated Earth, the manipulation of time. Even people who never saw a Dalek story before might be expected to have picked up that this was the kind of thing the Daleks did all the time in the 1960s.

The other reason why the Daleks are the right choice is because without them, this would only be the joint biggest danger the third Doctor has ever faced. After all, he already glimpsed an apocalyptic Earth in Inferno. The presence of the Daleks makes this unquestionably his most dangerous adventure yet. Because they haven’t just travelled back in time, changing history and conquering the Earth, but they’re also planning on taking over the universe. And while we can never quite believe that the dear old Master would ever actually succeed, the Daleks are another matter entirely. Before Day of the Daleks, the third Doctor has never had an adventure on the scale of his predecessors. Yes, he’s foiled invasions of Earth and megalomaniac plots. But he’s never had to battle an enemy that has already conquered the planet, or that will pursue him through time to his death.

Two years into his era, you’d be forgiven for having a niggling sense that the Doctor isn’t quite as good as he used to be; that when the Time Lords exiled him to Earth, they diminished him. Even the Daleks – who knew the second Doctor the instant they set eyes on him – don’t recognise this new version. Who can blame them? If you hadn’t seen the show since The Evil of the Daleks and you switched on to see radio comedian Jon Pertwee working for the British Army, you might be wondering what on earth has happened to the magic of Doctor Who.

But then the Daleks discover, to their obvious terror, that this is the same man that defeated their first invasion of Earth; who turned their Time Destructor on them, and brought about their apocalyptic civil war. He is absolutely the same man. And he isn’t diminished. If anything, he’s grown in stature. The way the third Doctor defeats the Daleks is unique. He doesn’t trick them, or lash up a gizmo, or turn their weapons against them. He appeals to the one thing in their last story they admitted they could never overcome – the human spirit. He stops the guerrillas from killing the Controller. That act of mercy, a word the Daleks don’t understand, is the salvation of the entire planet. The third Doctor doesn’t just defeat these Daleks, he stops them from even existing. A Doctor who’s been trapped on a devastated Earth, without his TARDIS and without the Brigadier, with no weapons and no plan. And he wins his most complete victory over his greatest enemies. No wonder they’re terrified of him. No wonder the past Doctors turn up to gaze benevolently down on their anointed successor, finally proving himself a more than worthy replacement.

Day of the Daleks is a fantastic story. It’s one of Pertwee’s best-ever performances. After a year when they were writing for a generic ditzy female assistant, the writers have now had chance to see what Katy Manning is capable of, and she gets to be resourceful, brave, and one of the all-time great companions. The script manages to make a potentially complicated idea easy to follow thanks to clever segueing between scenes and time zones. Most importantly, once and for all, it shows that this Doctor doesn’t need UNIT. And that’s surely got to be a deliberate choice by the production team. Last year, Colony in Space (deliberately the only past story referenced in this episode) showed that they could still do Doctor Who like it was made in the 1960s. This feels like a definitive step forward. Although UNIT appear, they’re sidelined: absent from the future Earth episodes, and barely interacting with the Doctor and Jo. Then they don’t even appear in the next three stories and when they do finally turn up again in The Time Monster they’re only useful for delivering the Doctor his TARDIS so he can go and have an adventure in history. Though they’ll appear in five more Pertwee stories, only two of those could really be compared to their Season Seven and Eight heydays. So, The Three Doctors is merely a tidying up exercise: it’s here that the line is really drawn under the trapped on Earth saga. With the Daleks back and the TARDIS more or less working, all the pieces are in place for the Doctor to resume his adventures in space and time. He’s back, and it’s about time.

Next Time: “Everything that ever hated you is coming here tonight. You can’t win this. You can’t even fight it…” A war is brewing on the Frontier in Space.

And for an alternative take on 1972 in Doctor Who visit Simon Guerrier’s excellent blog here

1971: Colony in Space

April, 1971. In the 15 months since the last blog entry, Doctor Who has settled into its new, Earthbound format. Season Eight began in January with a sequel to Spearhead from Space that was most notable for introducing a new Time Lord villain, the Master, who went on appeared in both subsequent stories. We’ve just finished The Claws of Axos, and had our first glimpse inside the TARDIS in colour. And then, sneaking in sheepishly to the season’s graveyard slot, there’s Colony in Space.

April, 1971. In the 15 months since the last blog entry, Doctor Who has settled into its new, Earthbound format. Season Eight began in January with a sequel to Spearhead from Space that was most notable for introducing a new Time Lord villain, the Master, who went on appeared in both subsequent stories. We’ve just finished The Claws of Axos, and had our first glimpse inside the TARDIS in colour. And then, sneaking in sheepishly to the season’s graveyard slot, there’s Colony in Space.

The title of the story tells you from the off that this is a break from the series’ new format. And if that’s not clue enough, the very first scene takes us back to the planet of the Time Lords, last seen in Hulke and Dicks’ The War Games. Reflecting on its decision to exile the Doctor to 20th Century Earth, the Time Lord tribunal realises that he is probably more useful to them if he has a degree of freedom. Particularly since the Master has stolen their secret files on the doomsday weapon.

We then cut to Earth where the Doctor and his new assistant Jo Grant indulge in a bit of business with the Brigadier, who’s still hunting the Master. Having been fiddling with the TARDIS dematerialisation circuit all season, the Doctor is convinced that he’s finally repaired it, and he intends to test it with a trip into space.

We’re then treated, in her fourth story, to Jo’s reaction to setting foot inside the TARDIS for the first time – a rite of passage that’s become a money shot for Twenty-First Century companions, but which, in context, we haven’t seen in the show since 1968 (Liz never even got to go through the doors). Let’s pause on this, because it’s an important moment. Jo claims that until this point, she’s never really believed all the Doctor’s wild stories about travelling in space and time. Which implies that as far as she’s concerned, he’s just a charmingly eccentric man who works for the Brigadier and fights aliens. Any kids watching, who can’t remember two years ago when the little dark-haired man was Dr. Who, are probably in the same boat. They’ve grown up with a series where the Doctor is a member of a military organisation defending the Earth. But, as the Doctor reminds Jo, and us, “Before I was stranded on Earth I spent all my time exploring new worlds and seeking the wonders of the universe.”

Terrance Dicks has frequently claimed that he was never a fan of the trapped on Earth format, and that it was Malcolm Hulke who pointed out to him that it essentially limited the scope of the show to two stories: alien invasions or mad scientists. For Season Seven, Dicks challenged Hulke to come up with another option, which he duly did – Doctor Who and the Silurians is probably the most creative solution to the problem. But that only takes it to three, and they have five slots to fill. So, again Dicks has challenged Hulke to come up with a new type of story. But instead, Hulke submits this: a return to the adventures in space and time of the Hartnell era.

This is absolutely the right moment to tell this story: the trapped on Earth formula is becoming repetitive, and although the Master has livened the show up, giving the Doctor a sense of purpose he lacked the previous year, Barry Letts and Terrance Dicks must have been aware that even this had a limited shelf life. Although Malcolm Hulke hadn’t written any of the second Doctor’s space adventures (Robert Holmes would have been the more obvious choice), the indications are that he was Dicks’ most trusted collaborator and therefore the writer of choice to write the pilot of the show Letts and Dicks want to make.

Even so, he doesn’t get it entirely right: aside from a bizarre flower Jo picks in the first episode, the planet Uxarieus is pretty dreary, and Hulke spends a lot of time showing how miserable and hard life is for the colonists. The last Earth colony we visited, in 1967’s The Macra Terror, was a much jollier place. These colonists fret about their crop, complain and the government and generally seem like the English working class transplanted onto another planet. Hulke shows his socialist credentials by having them be the victims of a rapacious corporation, IMC, which is willing to resort to terror tactics and murder in order to force them off their land and set up mining operations.

The main plot, a six-episode feud between colonists and IMC staff, largely consists of a series of reversals where one side temporarily gains the upper hand and holds the other at gunpoint, with a lot of wandering between the bridge of the IMC spaceship and the main dome of the colony. It all goes on far too long, and could have been better structured so that the story escalates in two episode chunks – the first pair focusing on the IMC attempts to scare off the colonists with their lizard robot, the second on the Master’s arrival and all the complications that creates, and the last on the real secret of the planet: the hidden city and its doomsday weapon. By running all three plots in parallel, Hulke makes the whole thing drag.

But that isn’t to say this isn’t a hugely influential story. Hulke’s view of Earth – a polluted and over-populated wasteland – becomes the standard future history of our planet as explored in subsequent space-based Pertwee episodes, while the environmental concerns raised here are further developed in The Green Death and Invasion of the Dinosaurs. These, in turn, inspire a later generation of writers who keep returning to the ideas – and the settings – in the New Adventures.

Another key change is that the Primitives aren’t evil monsters. They’re an alien civilisation. Malcolm Hulke’s Pertwee stories have already tried to get away from the simplistic Troughton era approach of alien equalling evil through having the Silurians and the alien Ambassadors being fundamentally no different than people. Pertwee’s greeting – “How do you do?” – to the alien priest in the hidden city is an obvious repeat of his cheery greeting when he first meets a Silurian, but it’s still a welcome change from the second Doctor, who was fundamentally suspicious and mistrustful of anything that didn’t look human. Here, the Doctor is genuinely excited to show Jo the strange glass paintings of the Primitives, attempting to understand their history, respecting their culture as he did the Aztecs’ or the Didonians’. And in the next year we get a story where the Doctor is shown to be wrong when he automatically assumes the Ice Warriors are evil, and another where the monsters are actually the good guys and it’s the Earth Empire that’s evil. All these suggest a production team keen to move beyond the simple morality of the Troughton episodes.

Then there’s the final showdown between the Doctor and the Master at the heart of the doomsday machine. The weapon is shown to have been responsible for causing mutations in the people of Uxarieus, and rendering the planet barren in another pointed reference to current affairs (as the Doctor points out, once doomsday weapons are developed they are usually deployed). While they’ve danced round each other in the past three stories, and it’s become customary for the Master to try to tempt the Doctor into joining him, their exchange in the sixth episode gets to the heart of their differences. “Look at all those planetary systems: we could rule them all,” says the Master. “What for? What’s the point?” replies the Doctor. “I want to see the universe, not rule it.” It’s such a nice line, Russell T Davies references it in the confrontations he writes for his Doctor and Master.

So, although as holidays go it’s more of a weekend in Bognor than a fortnight in Malta, Colony in Space is a powerful restatement of the basic principles of a series that is at risk of forgetting them. Despite its plodding plot, there is no way that this story could have been told in the trapped on Earth format. And although it introduces no memorable new monsters, its whole approach to exploring alien planets is more engaging than anything the series has done since the Hartnell era.

It’s easy to criticise Colony in Space, but I think it gets more right than wrong. And the audience seemed to like it as well – BBC execs apparently excitedly noted that the third episode’s ratings were the highest since The Daleks’ Master Plan in 1966, and it was selected as one of the earliest stories to be novelised. Most importantly, after two years of trapping the series on Earth and in the military, it’s the first UNIT-free story of the era, and, the parallel universe sections of Inferno aside, the first time we see the third Doctor operating as an outsider, without official papers or the back up of the Brigadier. The first time, in short, that he gets to play the Doctor in anything like the way his predecessors did. Next season, perhaps because of this story’s success, that’s going to become the norm. But there’s still one ingredient missing. One key element of the show that’s become crucial to defining the Doctor…

Next Time: “You are my enemy, and I’m yours. You are everything that I despise. The worst thing in all creation. I’ve defeated you time and again. I saved the whole of reality from you. I am the Doctor. And you are the Daleks…”

1970: Spearhead from Space

January, 1970. In the six months since Doctor Who went off the air, the biggest news has been the Apollo 11 and 12 Moon landings. Four human beings have walked on another planet, and looked up to see the Earth in the sky. Which makes the opening shot of this serial – our lonely planet, floating in the blackness of space – especially poignant.

January, 1970. In the six months since Doctor Who went off the air, the biggest news has been the Apollo 11 and 12 Moon landings. Four human beings have walked on another planet, and looked up to see the Earth in the sky. Which makes the opening shot of this serial – our lonely planet, floating in the blackness of space – especially poignant.

There’s something to be said for the argument that once we got to the moon and found nothing there, space lost its appeal slightly. Certainly, in the popular imagination the early 1970s are more notable for their introspection – meditation and mysticism – than the questing spirit of the 1960s. Having established that we were alone in the Solar System, if not the universe, there was suddenly an increased sense of urgency to protect our own planet. Environmentalism was on the rise, and series such as Doomwatch captured the mood of the times, where the biggest threat to humankind was our own short-sightedness.

On TV, Star Trek‘s voyage to strange new worlds, new life and new civilisations, ended in 1969. The biggest sci-fi movie franchise was the Planet of the Apes series, which, famously, was Earth all along. So ending the Doctor’s adventures in space and time and exiling him to 20th Century Earth fits very well with the zeitgeist. And as the first story in the new house style, Spearhead from Space is promising.

Given the persistent idea that the UNIT stories take place in the future, it’s interesting that in the first scene of the 1970s, a woman is in charge, giving a male radio operator a dressing down for his fanciful speculation. Blink and you miss it, but it’s an important detail: straight away, the show establishes that we’re in a time when women are the unquestioned equals of men. Later, the Brigadier is shown to be embarrassed by the chauvinist attitudes of a stuffy old British Army general, siding with the smartest person in the room – Dr. Elizabeth Shaw – rather than the most senior man. At this stage, the Brigadier is being set up very much as a ‘new man’, which ties back to The Web of Fear when he’s far more open than his colleagues to the possibility of a Police Box that travels in time and space. Given he’s later reduced to chauvinist comic relief, the Brigadier we get here is much more in the spirit of Haisman and Lincoln’s original creation, and a more interesting character.

Robert Holmes establishes the new set-up of the series with an economical two-hander between the Brigadier and Liz. Reiterating the predominant theme of the Troughton years – space is dangerous and the Earth is surrounded by alien monsters hungry for a piece of us – the Brigadier tries to convince Liz to become UNIT’s new scientific advisor. And fuelling the mood of paranoia and mistrust of politicians, he states, “There was a policy decision not to inform the public” about two previous alien invasion attempts.

So before we even meet the new Doctor, Holmes has established the Brigadier as the leading man in this show. There’s a hint that the new dynamic might be the Brigadier and Liz – who enjoy a slightly flirtatious relationship – being assisted by an eccentric alien Doctor, who’s a whimsical secondary presence, coming up with moments of genius in the lab: a sort of precursor to Dr. Walter Bishop in Fringe. This fits with reports that Derrick Sherwin wanted to cast a known comic actor to play the guitar and goof around. But all that’s put paid to the moment the new Doctor wakes up from his coma.

If Troughton was charismatic, and made the Doctor into the dominant lead of the series, then Pertwee just turns that up to 11. He dominates the screen, from the moment he starts pulling faces into Liz’s mirror. Taking Troughton’s occasional clowning and charm, and Hartnell’s screen-hogging arrogance, Pertwee is a presence in every one of his scenes. It’s impossible not to be drawn to him. Tom Baker, with an uncharacteristic hint of awe, described him as a glittering light bulb, and he was right. Any idea the producers might have had to make Courtney a lead are clearly untenable when Pertwee is so obviously the star of this show. Director Derek Martinus, one of the series’ best, has clearly clocked this, and gives the audience plenty of close ups of the new lead, and enough time to show his flair for comedy, for example in the shower scene. When the new Doctor drives up to UNIT’s secret headquarters and demands to see the Brigadier, you can practically see Derrick Sherwin – who’s playing the hapless security guard – roll over and surrender.

Of course it helps the new Doctor that his predecessor hasn’t been seen for six months, and that the last time we did see him he was at rock bottom, But nonetheless, even without a Ben or Polly to help the audience accept him, Pertwee establishes himself in the role remarkably quickly, and with none of the lingering suspicion that Troughton’s Doctor engendered.

While the audience has been focusing on the Brigadier setting up the new format and Pertwee taking over the show, in the background the Auton invasion has been unfolding quietly but methodically, the pieces dropping into place before things properly kick off in Episode Three. We ought to give Robert Holmes credit for this balancing act, because the big invasion story is really only a sideshow while UNIT and the new Doctor to set themselves up, and then an opportunity for them prove their mettle. However, this is only really problematic when you notice that the second and third cliffhangers involve bit-part actors being threatened because our leads aren’t really yet part of the invasion story.

It’s the fourth episode which gives us the money shot – one of the best of the entire run – when the Autons smash their way out of their window displays and start gunning down shoppers. This is the Yeti on the Loo scenario playing out in a way we’ve never really seen before – the War Machines shooting a man in a phone box are so out of the ordinary that they might as well be Daleks on Westminster Bridge. But this image takes what Doctor Who is good at – juxtaposing things that shouldn’t be together – and pushes it to a new level. This isn’t putting two very different things side by side: it’s putting the bizarre inside the mundane, thus making the everyday horrifying and uncanny. A shop window dummy that’s actually an alien robot is horrific in a way that a mythical abominable snowman that’s actually an alien robot isn’t. The genius of the TARDIS – an alien time machine inside a London police box – appropriated as the way to scare children.

Robert Holmes and Terrance Dicks clearly recognise this is the real innovation of Spearhead from Space, and to their credit when they re-make this story in the following season, the whole thing revolves around everyday objects being possessed by alien intelligence. Which results in Holmes getting his first rap on the knuckles for going too far into the realms of horror. Nevertheless, he clearly takes all the right lessons from this story when he becomes the show’s head writer.

So, this is clearly one of the classics, and it kicks off a highly-acclaimed season. Which might suggest that Derrick Sherwin’s instincts were right, that the show did need to go with the zeitgeist, and bring the Doctor down to Earth. In the short term, the approach works. However, looking at this story critically we have robot monsters collecting alien energy spheres to help manifest a disembodied intelligence. And we have monsters waking up and marching around London, while the Doctor and UNIT go to their factory with a gizmo that disrupts their brains. Yes, it’s a reductionist description, but the reality is there isn’t much here that hasn’t already been done in The Web of Fear or The Invasion. There’s even a dismantled Yeti sphere included in the Doctor’s Nestene-killing gizmo, while the Auton factory is exactly the same location as Tobias Vaughn’s factory. For all that, though, Spearhead from Space is unquestionably a success.

The real problem with the Earth exile format is that after 1970, it goes on for another two years. Once Season Seven has cycled through variations on Quatermass (Inferno tries to break the mould with a premonition story with sci-fi trappings), Season Eight struggles to find anywhere new to go. Hence we get two re-makes of this and another buried evil story. If anything, the miracle of the Pertwee era is that they managed to make a short-term decision, prompted by production problems and mounting costs, spin out so long. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with UNIT stories – after all, series like Doomwatch and UFO managed to get by just fine on a similar premise, and The X-Files ended up lasting for nine years – this in itself is telling. Other shows can do these stories as well as Doctor Who.

All along, the issue is staring us in the face. In the second episode, Liz re-states the basics of the series: “You really believe in a man who’s helped to save the world twice? With the power to transform his physical appearance? An alien who travels through time and space in a Police Box?”. The trouble is, she’s describing a show that’s more interesting than the one they’re making now. In the third episode, the Doctor and the Brigadier spend ages talking about the TARDIS – even though we’re not going to see it for another 15 months. Yes, you can do very good, even great stories about invasions of Earth. Spearhead from Space is one of them. But they’re not the only stories this series ought to be telling.

The Doctor showed us the dawn of man and the end of the world. We saw planets ruled by butterflies, and a land where every story was real. We visited China with Marco Polo and saw the Daleks on top of the Empire State Building. We’ve seen the wonders of the universe because of a madman with a box. But take his box away, and what do you have left?

Next Time: “Outside those doors, we might see anything. We could find new worlds, terrifying monsters. Impossible things…” After two years’ absence, Doctor Who returns in Colony in Space.

1969: The War Games

It’s April 1969. In the 14 months since the last blog post, the world has changed. In the USA, a string of political assassinations and the escalation of the Vietnam War precede the election of the Republican Richard Nixon. In France, student riots briefly threaten the right-wing government, which nevertheless triumphs in subsequent elections. While in the UK, the Conservatives surge ahead of Labour in the polls, and, the day after Episode One of The War Games airs, troops are deployed to Northern Ireland to reinforce the RUC.

It’s April 1969. In the 14 months since the last blog post, the world has changed. In the USA, a string of political assassinations and the escalation of the Vietnam War precede the election of the Republican Richard Nixon. In France, student riots briefly threaten the right-wing government, which nevertheless triumphs in subsequent elections. While in the UK, the Conservatives surge ahead of Labour in the polls, and, the day after Episode One of The War Games airs, troops are deployed to Northern Ireland to reinforce the RUC.

Across the Western world, after a decade of youthful rebellion, 1969 is the moment when the conservative Establishment reasserts its authority. Doctor Who has been ringing the changes as well. After The Web of Fear, Haisman and Lincoln’s next script is a stinging rebuke to the All You Need is Love generation, and while the Earth under siege format’s still going strong in The Invasion and The Seeds of Death, it’s been joined by odder offerings like The Mind Robber, The Krotons and The Space Pirates – the last two by Robert Holmes, the author of episodes of the weird alien invasion serial Undermind and the Quatermass-inspired movie Invasion.

Then there’s The War Games: the climax of both Troughton’s tenure, and Doctor Who in the 1960s. There are some very obvious things to say about this: at 10 episodes, it’s the longest serial since 1966. It’s the first story with Terrance Dicks’ name in the titles. He’s going to be the writer with the longest association with the series, and you can already see his respect for continuity in the scenes where he has Zoe and Jamie returned to their own times. It’s exceptionally well directed by David Maloney. And it introduces the Time Lords and sets up the third Doctor’s exile to Earth.

All these are true facts. But there are also some commonly-repeated fallacies. This isn’t the first story to be set in Earth’s history since 1967, because it isn’t set in Earth’s history, but on an alien planet. That’s important, because throughout Troughton’s era, we’ve seen that the Earth is the default destination for the TARDIS – the Doctor even comments on it in The Web of Fear. So it’s a marvellous twist when it turns out that this isn’t Earth, and that the Doctor has become caught up in events that transcend one planet and one time. Previous sci-fi/historical mash-ups have depended on placing something anachronistic into Earth’s past. The War Games flips this by placing Earth’s past into a sci-fi story: a trick that the series won’t convincingly pull off again until Enlightenment.

Another fallacy says the story is a nine episode story plus a practically stand-alone, one-part epilogue. However, that’s nonsense: the tenth episode is absolutely integral to everything that has gone before. This last point’s important, because some commentators have suggested that focusing on the last episode and ignoring the first nine is a mistake. And to an extent they’re right – why would you ignore the first nine episodes when they’re as compelling and brilliant as Doctor Who gets? But the fact is, they are a lead-in to the final showdown – just as the first six episodes of The Evil of the Daleks are only meaningful as a set-up to the confrontation with the Emperor and the Dalek civil war.

Terrance Dicks and Malcolm Hulke make the story a gradual escalation. It begins with the TARDIS arriving in what looks like the First World War – and the Doctor immediately decides it’s far too big a problem for him to solve, and wants to just leave. Then it’s revealed that somehow there are Romans on the battlefield. Then that there’s mind control involved. Then that there are aliens involved. Aliens with TARDIS-like devices. Another one of the Doctor’s people. A plot to conquer the universe. And, finally, an intervention by the Doctor’s own people. There’s easily enough plot there to justify the 10 episodes, with revelations dropped in at regular intervals. The point being, by the end of Episode Nine, without us even seeing it happen, the stakes have got so huge that they’re beyond the Doctor’s ability to handle. It’s a neat way of bringing the story – which begins with the Doctor trying to run away from an insoluble problem – full circle. And it immediately establishes the Time Lords as a credible power because they can succeed where the Doctor has failed.

The final episode wraps up the plot quite cleverly, by having the Time Lords run their own version of the Nuremberg trials and condemn the warmongers to dematerialisation. The universe is saved, and the kidnapped human beings are returned to their own times. However, just as the Establishment is reasserting itself in the real world, so the Time Lords impose themselves on the Doctor’s universe.

Because, the 1960s ended in failure. The Summer of Love and the 1968 revolutions failed. The optimistic belief that youth could change the world was shot down. The War Games reflects this. The Doctor looks shabbier than ever before – coat ripped, trousers torn, hair a mess. He looks like he’s coming apart at the seams. Threatened by the Time Lords, he just seems impotent. Strangers wander in and out of his TARDIS; the War Lord tries to take it over, and the Doctor stands by and wrings his hands. This is abject. Even his final attempt to escape, through the strange, Tara King Avengers style sets of his home planet, is half-hearted.

Of course he mounts a defence of himself – bringing up images of his most iconic enemies – Daleks, Cybermen, Ice Warriors, Yeti and, yes, the deadly robot Quarks (they were still flogging that dead horse right to the end). But he crumbles in the face of the greatest monsters of all. I’ve previously suggested that since The Evil of the Daleks, the producers have been searching for the next big monster. Terrance Dicks gives it to them. A people that stand by and do nothing while the Daleks wipe out billions; a people that smile as they wipe you from existence, and a people that are more interested in stifling revolution and preserving their own power than helping anyone else. No wonder the Doctor ran. These Time Lords are horrifying: the very embodiment of the deadening forces of conservatism sweeping the globe, crushing the spirit of youth. The British director Pete Walker made a series of horror films in the 1970s exploring similar themes, and over in the USA George A Romero had just made a starkly nihilistic zombie movie in which the hero is killed not by the monsters, but by the National Guard on the clean-up operation. Terrance Dicks and Malcolm Hulke tell us that the real monsters aren’t besieging us. They’ve been inside the base all along.